Canada’s healthcare system is known for being free and fair. That part isn’t in question. But when it comes to speed, the picture is not so simple. Patients often wait weeks just to get a diagnosis or begin treatment, and it’s only gotten worse with time.

In 2023, the average wait between seeing a general doctor and receiving specialist care was 27.4 weeks. That’s the longest ever recorded.

This article looks at why wait times in Canada are so long, what’s causing the delays, and how it affects people across the country.

We’ll also look at what hospitals and clinics can do to reduce the wait without adding pressure on already stretched teams.

Inside Canada’s Growing Hospital Wait Time Crisis

Wait times across Canada are stretching to new highs. In 2022, patients waited a median of 27.4 weeks between seeing a family doctor and receiving treatment, a rise from 25.6 weeks in 2021. Some specialties see waits of nearly 59 weeks. Diagnostic tests have long delays too—CT scans can take over five weeks, and MRIs often exceed 10 weeks

The COVID-19 pandemic made this worse. Surgery volumes dropped by around 14% from March 2020 to September 2022. Many procedures, like hip and knee replacements, now take longer to recover from than before .

Common Experiences of Patients

Long waits touch almost every patient at some point. People in ERs share stories of sitting for over 11 hours before seeing a doctor. Specialist referrals and routine surgeries are delayed for months. Reports like Waiting Your Turn document rising delays across provinces and departments.

These delays contribute to more pain, stress, and uncertainty. Some conditions worsen while patients wait. For many, getting help means waiting in limbo—and that can take a toll.

Why Are Wait Times so Long in Canada: Key Reasons

Canada’s long hospital wait times aren’t just about high demand. There are deeper, structural reasons that limit how quickly patients can get care. Let's look at a few reasons as to why are wait times so long in Canada:

1. Limited Private Sector Participation

A big reason behind Canada’s long hospital wait times is how limited the private sector’s role is in healthcare. The Canada Health Act puts strict limits on private services that overlap with what the public system covers. This means even when private clinics could ease the load, they’re often not allowed to.

Most people end up waiting in the same public queue, no matter how urgent or routine their need is. That builds pressure on hospitals and slows everything down.

Here’s what this leads to:

Patients can't turn to private clinics for faster care

Scans and surgeries get delayed because there's no backup

Long queues form when the system gets overwhelmed

Hospitals can't scale up easily, even when they need to

2. Shortage of Medical Professionals and Equipment

Another reason behind the long wait times in Canada healthcare is the simple lack of people and tools. There just aren’t enough doctors, nurses, or technicians to keep up with growing demand. According to OECD data, Canada ranks low among developed countries for doctors per capita. That gap becomes even harder to manage in rural areas or during flu season.

It’s not just staffing. Equipment shortages also slow things down. People wait weeks or even months for MRIs or ultrasounds—not because of high demand alone, but because there just aren't enough machines to go around.

This leads to:

Fewer appointments available each day

Delays in getting diagnosed and starting treatment

Hospitals stretched too thin, especially in emergencies

Long waiting time in hospitals even for urgent scans or beds

3. Fragmented Provincial Systems

Canada doesn’t have a single healthcare system. Each province runs its own, which means how fast you’re seen depends on where you live. Some provinces move quicker. Others don’t. And because there’s no shared system, nothing really connects them.

Hospitals can’t shift resources between provinces when demand spikes. A long wait in one place doesn’t get any easier just because another region has room. Patients end up stuck in silos, waiting longer than they should.

This leads to:

Big differences in treatment wait times from one province to another

No shared system for managing patient backlogs

Longer delays just because of your postal code

Long wait times in Canada healthcare without a single plan to fix it

4. Poor Technology Adoption and Queue Mismanagement

Many hospitals in Canada still rely on outdated systems. Paper forms, manual sign-ins, and disconnected tools slow everything down. Staff spend more time tracking down information than helping patients move forward.

There’s also no unified way to manage queues or waitlists. Every department might follow its own process, which adds confusion and delays that could be avoided with better coordination.

This results in:

Appointments getting missed or delayed due to manual errors

Patients waiting longer because there's no real-time status tracking

No clear view of who’s next or how long the wait actually is

Long waiting time in hospitals that could be reduced with proper queue tools

Improving Canada Healthcare Wait Times: What Needs to Change

Fixing long wait times in Canada’s healthcare system won’t happen overnight. But there are clear steps that can reduce delays and improve patient flow. One of the most immediate ways to make progress is through better use of technology.

1. Invest in Technology and Queue Management Systems

One of the fastest ways to reduce long waiting time in hospitals is by fixing how people line up for care. And no, this doesn’t mean bigger waiting rooms. It means smarter systems that actually track who’s waiting, for how long, and what needs to happen next.

Right now, many hospitals in Canada still rely on clipboards, phone calls, or sticky notes to manage patient flow. That’s part of the reason why wait times feel so unpredictable.

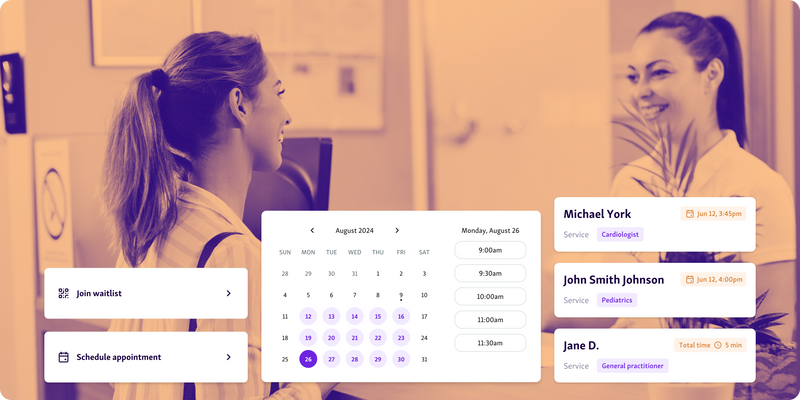

Queue tools like Qminder can help fix this.

Patients can check in digitally and see their place in line

Staff get a real-time view of all waiting patients

No more confusion about who’s next or how long the wait will be

It cuts the back and forth and helps reduce patient frustration

Instead of sitting and wondering, patients stay informed. Instead of guessing, staff work with real numbers. And that’s how a simple tool can start making long wait times in Canada healthcare less of a norm.

2. Adopt Single-Entry Models

A big reason for the long wait times in Canada healthcare is how people get into the system in the first place. Most referrals go into separate lines for each doctor or clinic. Some lines move fast. Others barely move at all. That’s where single-entry models come in.

Instead of having 10 separate lines, all patients enter a common waitlist and get matched with the next available provider.

This approach helps:

Make the process fairer for everyone

Prevent one doctor’s list from getting overloaded

Use time and resources more evenly across the system

Cut down long waiting time in hospitals caused by uneven backlogs

It doesn’t change the number of doctors, but it does make better use of the ones already in place. And that can make a big difference when every day of waiting counts.

3. Enable Team-Based Care and Skill Redistribution

One way to reduce long wait times in Canada healthcare is by rethinking who handles what. Not every case needs a specialist. But when everything funnels through them, it slows down care for everyone.

Team-based care spreads the load. Nurses, physician assistants, and other trained clinicians can step in for routine care, screenings, and follow-ups.

This approach helps:

Free up specialists to focus on complex cases

Shorten referral and treatment delays

Improve access without needing more doctors immediately

Ease long waiting time in hospitals without affecting care quality

Used well, it’s a practical fix that gets patients seen faster and helps the system work smarter with the staff it already has.

4. Make Wait Time Data Public and Transparent

Patients can’t make informed choices if they don’t know what to expect. When hospitals keep wait time data private, it only adds to the frustration.

Publishing estimated wait times helps people plan better. It also builds trust.

Here’s why it matters:

Patients know if a delay is normal or worth following up on

Transparency puts pressure on systems to improve

It helps reduce anxiety during long waiting time in hospitals

Makes the problem visible, which often leads to action

Some regions already show ER wait times online. It’s a small step, but one that can go a long way in improving Canada healthcare wait times.

Managing Long Wait Times in Canada Starts with Better Systems

Canada’s long waiting time in hospitals is no longer just a patient complaint. It’s a system-wide challenge that needs serious attention. From staffing shortages to fragmented provincial policies, the reasons are layered—but not unsolvable.

Better coordination, smart staffing, and better use of technology can bring real change. Queue management systems are already helping hospitals handle high volumes and reduce patient frustration.

Qminder stands out as a practical and proven solution. It gives hospitals real-time control over patient flow and helps people feel seen, not stuck.

Looking to improve how your hospital handles wait times? Book a Qminder demo today.

Bring a government-issued ID, your health insurance card, a list of current medications, relevant medical records or referrals, and any previous test results if available.

Yes, patients in Canada have the right to request a second medical opinion. It’s a common and acceptable part of ensuring you're confident in your diagnosis and treatment plan.

No, hospital parking fees are typically not covered by public health insurance plans. These costs are usually the responsibility of the patient or visitor.