If you’ve ever waited too long for customer service, you’ve already experienced the problem queuing theory tries to solve. At its core, queue theory looks at how lines form, why they break down, and what actually reduces wait times instead of just shifting them around.

From call centers to DMV customer service, the same patterns show up again and again: uneven arrivals, limited staff, and poor flow design.

By applying queuing theory and even a basic queuing theory formula, businesses can understand where delays come from and how to fix them without burning out staff or frustrating customers.

In this blog, we’ll break down how queuing theory applies to real-world customer service and why it matters more than most teams realize.

What Is Queuing Theory?

Queuing theory is a way to understand how lines form, how they move, and why they sometimes spiral out of control. In simple terms, queue theory looks at the relationship between customer arrivals, service speed, and waiting time. It helps explain common customer service problems like long waits, overwhelmed staff, and sudden backups that seem to appear out of nowhere.

The foundations of queuing theory were developed decades ago to manage phone networks and transportation systems, but the logic still applies today.

One of the most common ideas comes from a basic queuing theory formula known as Little’s Law:

L = λ × W

Where:

L = average number of customers in the system

λ = average arrival rate

W = average time a customer spends waiting or being served

This formula shows why balancing demand, service capacity, and waiting time matters. The goal isn’t eliminating waits entirely, which usually leads to overstaffing. It’s finding the point where service stays efficient without over- or under-serving customers.

You might also like - Queueing Theory vs. Practical Queue Management: What Public Sector Agencies Can Learn

Key Components of a Queueing System

Every queue, no matter how simple or complex, is built from a few core elements. Queuing theory focuses on these building blocks to explain why some queues move smoothly while others fall apart under pressure.

-

Arrival Rate

Arrival rate describes how often customers show up for customer service. The problem usually isn’t the average number of arrivals, it’s the variability. When many customers arrive at once instead of evenly over time, queues grow fast, staff get overwhelmed, and wait times spike. This is why places like DMV customer service struggle during peak hours even if they’re properly staffed on paper.

-

Service Rate

Service rate refers to how quickly staff or systems can handle customers once service begins. In queuing theory, even small slowdowns at the service point can create long waits when demand is high. In real-world customer service, service rate often changes throughout the day based on staff experience, task complexity, and interruptions.

-

Queue Length and Waiting Time

Queue length is how many people are waiting, while waiting time is how long they actually wait. Queue theory also highlights the gap between real wait time and perceived wait time. Uncertainty, lack of updates, and poor visibility often make waits feel much longer than they really are, especially in places like DMV customer service.

-

Number of Servers

The number of servers refers to how many staff or service points are available at the same time. In queuing theory, single-server systems behave very differently from multi-server setups. Adding servers can improve flow, but only if demand and service rate are balanced. Otherwise, more staff doesn’t always mean shorter waits.

Also read - What is Queue Management System? A Definitive Guide

Common Queuing Models Used in Customer Service

In queuing theory, models describe how customers arrive, wait, and get served. You don’t need math to understand them. Each model simply represents a real-world customer service setup and explains why queues behave the way they do.

1. Single-Server Queues (M/M/1)

The M/M/1 model represents a system with one service point and a single line. Customers arrive randomly and are served one at a time. This setup is common in small offices, front desks, or basic help desks.

Key characteristics of this model:

One staff member or service counter.

One queue shared by all arriving customers.

Random arrival times and variable service duration.

Why this matters in practice:

If arrivals increase even slightly, wait times rise fast.

Any slowdown at the service point affects everyone in line.

There’s no flexibility to absorb demand spikes.

In queue theory, M/M/1 explains why single-server environments feel fragile. In customer service settings, it shows why adding a second server or redistributing tasks often has an outsized impact on reducing wait times.

2. Multi-Server Queues (M/M/c)

The M/M/c model represents a queue with multiple service points serving a single line. Customers arrive randomly and are routed to the next available server. This setup is common in DMV customer service, hospitals, banks, and call centers.

What defines this model:

One shared queue with multiple staff members.

Customers are served by the first available server.

Service speed can vary between staff.

Why it works better for high-volume customer service:

Demand spikes are absorbed more easily.

Wait times are more stable than single-server systems.

The system is more resilient when one server slows down.

In queuing theory, M/M/c explains why multi-server setups scale better as traffic increases, especially in unpredictable environments.

3. Priority Queues

Priority queues are used when not all customers should be treated the same. In queue theory, certain arrivals are given higher priority based on urgency, status, or service type, while the rest continue to move through the normal flow.

Common use cases include:

Emergency or urgent cases in healthcare.

Special services in DMV customer service.

Technical escalations in support queues.

The key challenge is balance. Queuing theory shows that priority systems must be designed carefully. If too many customers jump the line, overall flow breaks down. When implemented correctly, priority queues handle urgent needs without significantly increasing wait times for everyone else.

Behavioral Dynamics in Queuing Theory

Queuing theory goes beyond math and models how customers actually behave when waiting. These behaviors are central to customer behavior in queuing theory because they directly influence wait times, queue stability, and overall service outcomes.

1. Balking in Queuing Theory

In queuing theory (also known as queue theory), balking refers to a customer choosing not to enter a queue at all. In customer service environments, this usually happens when the wait looks too long, too uncertain, or not worth the effort.

Balking is driven by perception, not calculation. While a queuing theory formula can estimate wait times, customers react to what they see. Crowded spaces, slow movement, or unclear flow often trigger balking, especially in high-volume settings like DMV customer service.

Operationally, balking is hard to track because the customer never enters the system. In queue theory, high balking rates often indicate:

Poor visibility into expected wait times

Service capacity not matching demand

A gap between perceived effort and service value

To eliminate balking in queuing theory, the focus should be on reducing uncertainty at the entry point. Display clear wait-time estimates, show queue progress, or let customers check in digitally instead of judging the line visually. In customer service and DMV customer service environments, removing guesswork is more effective than trying to shorten the line itself.

2. Jockeying in Queuing Theory

In queuing theory, jockeying occurs when a customer switches from one queue to another in hopes of being served faster. This behavior is common in customer service environments where multiple lines exist and progress appears uneven.

Jockeying is usually triggered by visible differences between queues. Customers compare movement speed, staff behavior, or queue length and make quick judgments. Even when a queuing theory formula shows average wait times are similar, perception drives action. In places like DMV customer service, this often leads to line hopping and confusion.

From a system perspective, jockeying introduces instability. In queue theory, frequent switching can:

Increase perceived unfairness among customers

Disrupt service flow and staff rhythm

Make wait times feel longer, even when they aren’t

Jockeying is best eliminated by removing the customer’s need to choose a line. Queue theory consistently favors a single, pooled queue that feeds the next available agent. This structure improves fairness, prevents line-switching, and increases throughput without requiring changes to staffing or queuing theory formulas.

3. Reneging in Queuing Theory

In queuing theory, reneging describes what happens when a customer leaves a queue after already joining it, before receiving service. This behavior appears when waiting exceeds what the customer is willing to tolerate.

Reneging is closely tied to time perception. Even if a queuing theory formula suggests the wait is within acceptable limits, customers may leave if progress feels slow or uncertain. In customer service environments like DMV customer service, long, unpredictable waits are a common trigger.

From a queue theory perspective, reneging creates hidden inefficiency. The system invests time managing the customer, but service capacity is never realized. High reneging rates often point to:

Long or unpredictable wait times

Lack of updates during the wait

Poor alignment between demand and staffing

Reducing reneging requires keeping customers informed once they are in the queue. Real-time updates, progress indicators, and clear service expectations help customers stay committed. In high-pressure customer service settings like DMVs, visibility matters more than speed when preventing walkouts.

4. Customer Behavior in Queuing Theory

In queuing theory, customer behavior explains how people react to waiting, not just how long they wait. It brings together behaviors like balking, jockeying, and reneging to show how real human decisions shape queue performance.

A queuing theory formula can model arrival rates and service capacity, but customer service outcomes depend heavily on perception. Customers judge fairness, progress, and effort based on what they see and feel, not on averages. In environments like DMV customer service, where stress and urgency are high, small frustrations quickly turn into visible behavior changes.

From a queue theory perspective, customer behavior affects:

Actual throughput versus theoretical capacity

Queue stability and predictability

Perceived service quality, even when wait times are similar

Managing customer behavior in queuing theory means designing systems around perception, not averages. Clear rules, predictable flow, and transparent communication reduce frustration even when waits exist. Aligning system design with how people experience time delivers better results than relying solely on a queuing theory formula.

Applying Queuing Theory in Modern Customer Service

Queuing theory is most valuable when it informs real operational choices. In modern customer service, it helps teams design systems that handle unpredictable demand while keeping wait times and staff stress under control.

-

Designing Better Waiting Experiences

Queue theory explains that uncertainty makes waits feel longer than they are. When customers can see progress, get updates, or understand what’s happening, perceived wait time drops even if actual service speed doesn’t change.

-

Matching Staffing to Demand Patterns

Instead of staffing based on averages, queuing theory encourages planning around peaks and variability. This leads to better coverage during busy periods and fewer wasted resources during slow times, which is especially important in high-traffic environments.

-

Separating Walk-Ins and Appointments

Combining walk-ins and appointments without structure often creates breakdowns. Queuing theory supports separating or carefully balancing these flows so scheduled customers aren’t delayed and walk-ins don’t overwhelm the system.

How Technology Bridges the Gap Between Theory and Reality

Queuing theory explains why queues behave the way they do. Technology is what makes those ideas usable in real customer service environments. Digital tools turn theory into day-to-day decisions that actually reduce wait times, smooth flow, and protect staff capacity.

1. Real-Time Queue Visibility

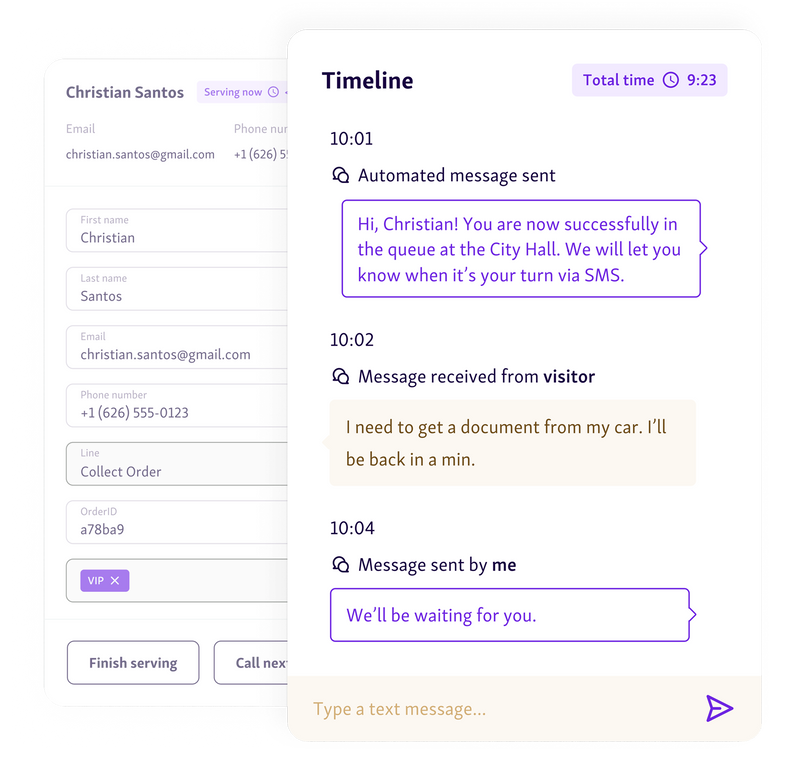

One of the biggest gaps between theory and reality is lack of visibility. Real-time queue visibility gives staff and customers live SMS updates or waiting room TV displays on queue length, wait times, and who’s being served. This directly addresses a core queue theory problem: uncertainty. When everyone can see what’s happening, perceived wait drops, interruptions decrease, and staff can react before queues spiral.

2. Virtual Queues and Remote Check-In

Queuing theory shows that physical lines amplify frustration without improving flow. Tools like Qminder offer virtual queues and remote check-in let customers wait off-site while keeping their place in line. This applies theory in a practical way by separating waiting from service capacity, reducing crowding without changing arrival rates.

Read more - How Remote Check-In Simplifies Visitor Management

3. Data-Driven Flow Optimization

Theory relies on understanding arrival patterns and service rates over time. Qminder’s analytics and service intelligence data make this actionable by showing peak hours, average service times, and recurring bottlenecks. Managers can plan staffing and service capacity based on real demand instead of assumptions, which is exactly what queuing theory has always aimed to solve.

Turning Queuing Theory Into Better Customer Service

Queuing theory isn’t just an academic concept. It explains why long waits happen, why systems break under pressure, and why effort alone doesn’t fix customer service problems.

By understanding arrival rates, service capacity, and utilization, teams can design queues that handle real-world variability instead of reacting to it. When theory is supported by the right tools, it becomes practical and actionable.

Platforms like Qminder help turn queue theory into day-to-day improvements with real-time visibility, virtual queues, and data-driven planning.

If you want shorter waits and calmer service environments, it’s time to apply queuing theory with Qminder.

No. While queuing theory is often associated with places like DMV customer service, it’s just as useful for smaller teams. Even low-volume environments benefit from understanding variability, service limits, and why occasional spikes cause delays.

Yes. Queue theory helps explain why customers may feel the system is unfair, even when it’s technically working as designed. Issues like unclear rules, invisible progress, or mixed service types often trigger frustration more than the actual wait time.

Absolutely. The same principles apply to chat support, email queues, and call centers. Arrival rates, service capacity, and utilization still determine wait times, even when the “queue” isn’t physical.